A few years ago, I was hanging out the side of an airplane, 3,000 feet above the ground, speeding at almost 150 miles per hour. That’s never my favorite place to be, careening through the sky leaning out of a plane, but I had good reason. I was shooting 4K video of an airshow pilot flying with us in close formation. The spinning prop of his flying hot rod, clawing the air at roughly 2,500 RPM, was barely more than ten feet from my head. And while I’m glad we had smooth air, it was also just another day at the office.

I was using one of Sony’s then-new 4K camcorders, and once back on terra firma and sitting in front of my Mac, the footage looked amazing. So good in fact, that when I screened some footage on a 4K display, I felt like I could reach into the monitor and run my hand along the smooth, composite wing.

When I delivered the final short film to the airshow pilot, I also sent him a few beautiful still shots that I rendered from the footage. These still frames looked about as good as any shot from a professional DSLR. And that got me thinking about shooting a fashion or beauty story with a 4K motion picture camera with the specific intent of only pulling stills. So I did just that, and I’ve been pulling stills from 4K video files ever since.

Capability, Demand & Resolution-The Beginning of Convergence

For most of my career, I’ve been a still photographer, specializing in celebrity portraits, fashion, beauty, aviation and rodeo. In the past few years however, I’ve also transitioned to motion, and last year I was producer of, and shot, a couple feature films. One of those films, Three Days in August, premiered this spring at the Dallas International Film Festival. It also is the very first theatrical feature shot exclusively on a Sony Alpha camera, the α7R II.

When I did those airplane and fashion shoots back in late 2013 and early 2014, I used the large-sensor Sony F55 digital cinema camera—it was one of the few cameras capable of doing it at the time. 4K resolution is either 3840 x 2160(UHD) or 4096 x 2160(DCI). This resolution works out to about 8.3 megapixels per frame. I figured this would likely be enough resolution to pull stills of sufficient quality to run in magazines, especially with a little tweaking in Photoshop—and it worked great. Today I do the same thing with my α7R II, α6300 and α7S II cameras.

Lately, more and more clients are requesting motion content in addition to still photographs. This convergence of stills and motion has been building for a few years now and shooting video and editing is something many photographers should be adding to their skill set.

How To Do It

One of the first things fledgling videographers learn are the camera settings for video vs. still shooting. One of the main rules of thumb is to use a shutter speed that is twice your frame rate. This gives us an equivalent 180 degree shutter angle and what is considered a cinematic look. Central to this cinematic look is a slight amount of motion blur. Since I wanted to maximize the number of frames I would have to choose from, I decided to minimize motion blur and capture clear, defined images.

To minimize the motion blur for my fashion shoots, I select a higher shutter speed than the standard 1/50-sec. that would normally correspond to my 24 fps frame rate. This higher shutter speed is fast enough to limit blur, yet still slow enough to show a bit of motion in moving hair, for example. I strongly suggest doing some camera tests on your own to determine which shutter speed gives you whichever desired effect you seek. Having some good ND filters on hand is also extremely helpful for getting your camera and lens settings where you want them.

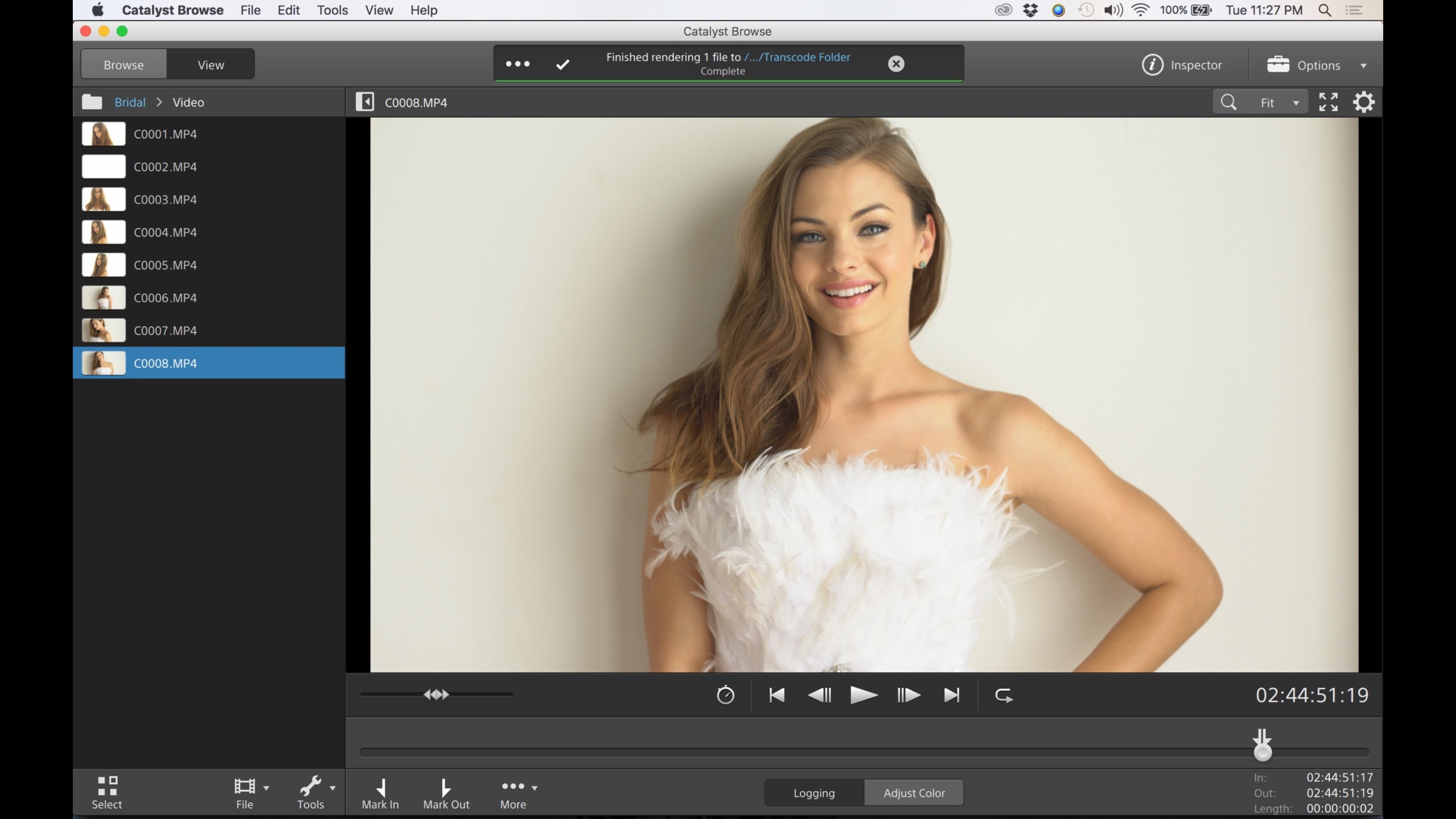

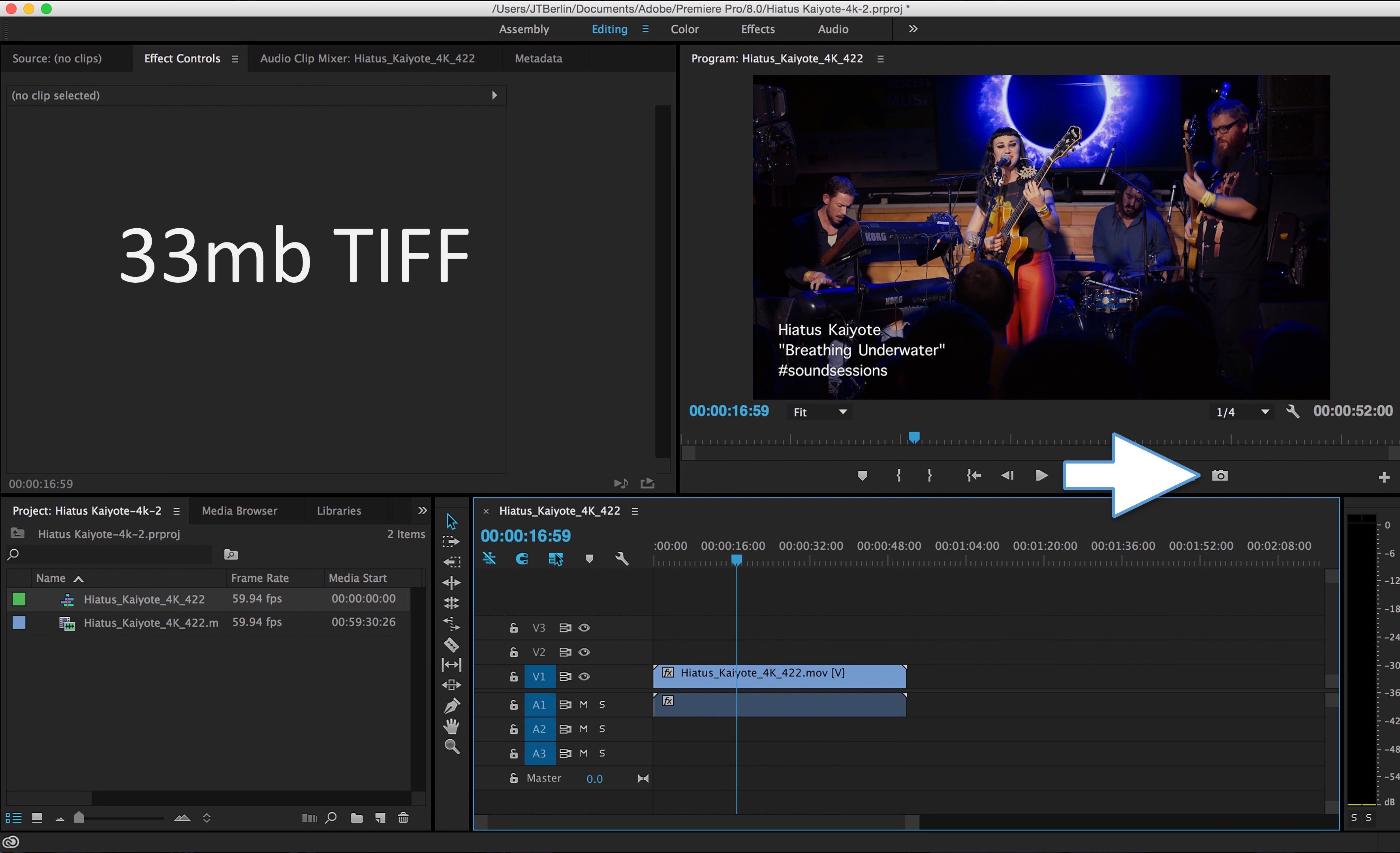

Once I have the footage I use a free application called Catalyst Browse to scrub through sequences and find the frames I want to render as stills. Adobe Premiere Pro also has a button with a camera icon that will render a TIFF right from your timeline. I’m not that familiar with the feature set of other NLE solutions so I can’t comment further on that. I prefer the simplicity of Catalyst Browse, particularly if I’m specifically looking to pull stills.

Above: Catalyst Browse, Adobe Premiere Pro

I’ve also learned that as I comb frame by frame through my selects, there’s a fine balance between the ability to capture the perfect moment over and over at 24 fps, and overkill. I think the key is to not overshoot – I keep my model moving and I have them pause ever so slightly at key moments to ensure I get the shot.

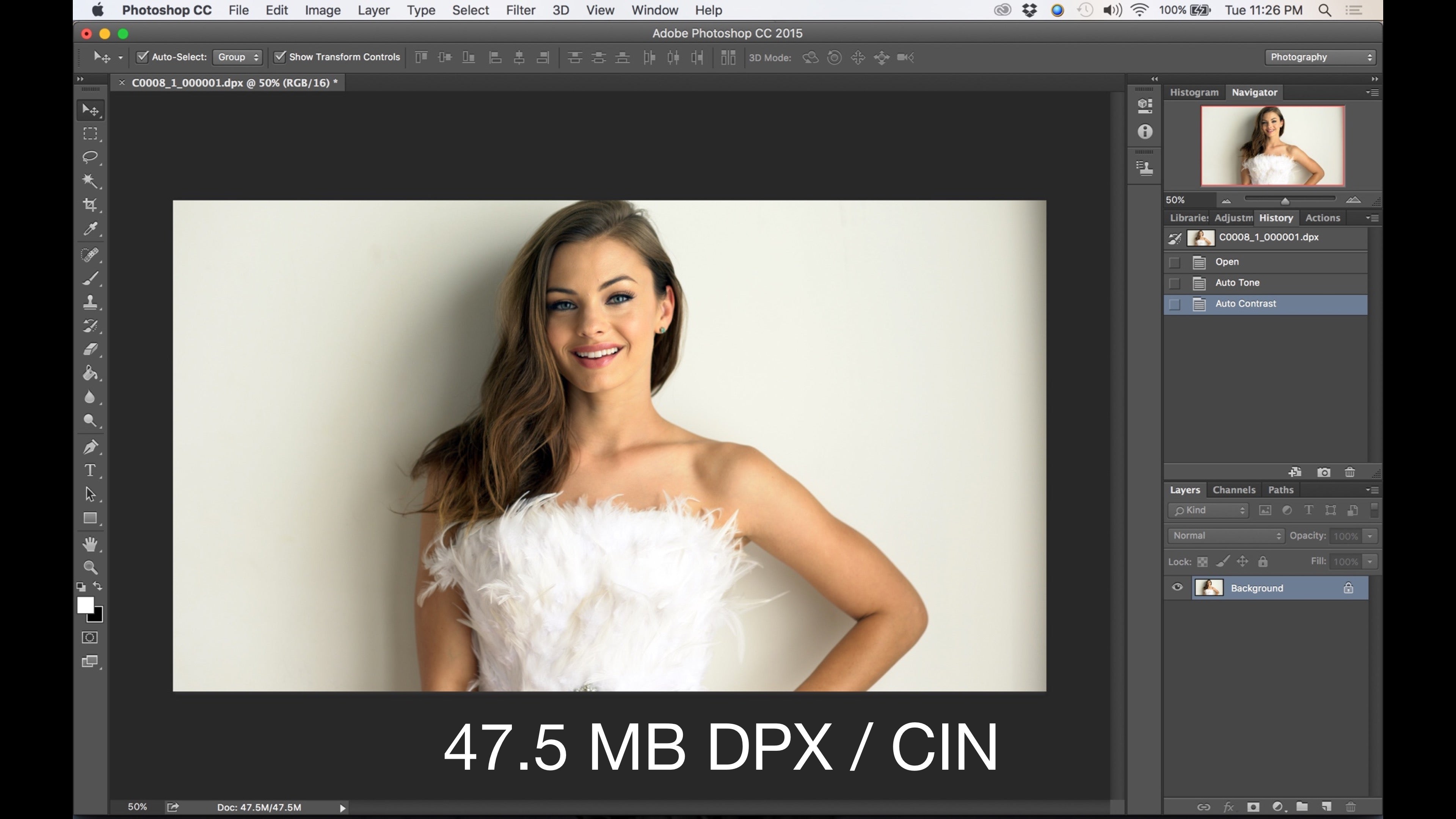

Once I make selects on my timeline, I mark each single frame as both “in” and “out” point and process them in Catalyst Browse as DPX files. Each DPX file from my Sony α7R II internally recorded 4K comes out to a bit over 47 MB and is recognized by, and opens right up in, Adobe Photoshop. After a proper retouch, I’ll save a TIFF as my final for submission to the client and a smaller JPEG for social media and other use. I’ll also save a version of the DPX to file as my digital negative of sorts. Photoshop saves DPX as Cineon files.

This motion to stills workflow is very similar to the post-production process I normally use on a photo project. For example, I’ll import RAW files from my Sony α7R II camera into my Mac, edit and color grade my RAW selects with Phase One Capture One, and then render those files as high resolution TIFFs for further refinement and retouching in Photoshop.

One thing that became more top of mind when working with a model with this technique is that when the camera is rolling, unlike when I’m shooting just shooting stills, there is no click of the shutter. My model direction, I found, has to be continuous and even more specific than it usually is because many models rely on the click of the shutter for everything from affirmation to pace and momentum. Without the feedback of that click, I was in a constant monologue with my model and I could see, for her, it was also an adjustment that took a short while.

I see "cinephotography" becoming increasingly popular and another option for photographers seeking to take the convergence of stills and motion to the next level, for the technology is here.