Indigenous Motherhood is an emerging photo series and individuated part of Zoe Urness' larger body of work, Keeping the Traditions Alive. For this part of the series, Alpha Female+ grant winner Urness returned to the Pacific Northwest where she was raised in order to give birth to her daughter, and was inspired to turn her camera on indigenous motherhood. Over the past five weeks, she visited coastal and inlet tribes to capture the stories of different stages of motherhood. Urness photographed indigenous mothers wearing regalia in varied landscapes to represent the deep connection to mother Earth and to their cultural traditions. Learn more about her Alpha Female+ grant-winning project below.

Why Sepia?

In my fine art photography career I have primarily used black and white 120mm medium format film and printed with a sepia tone treatment. I found using the Sony equipment made my images vibrant and almost matched what your eye sees naturally, a large contrast to the natural and grainy quality I value when shooting on film. This camera has me excited to explore my process in color further outside of this grant experience. Over these past several weeks, I feel that the varied landscapes, including the use of the underwater Sony camera in addition to the use of artificial lighting in some of the images, enabled me to bring out new elements in my work. Ultimately the sepia tone treatment allows the work to look cohesive and is a natural continuation of my overarching method.

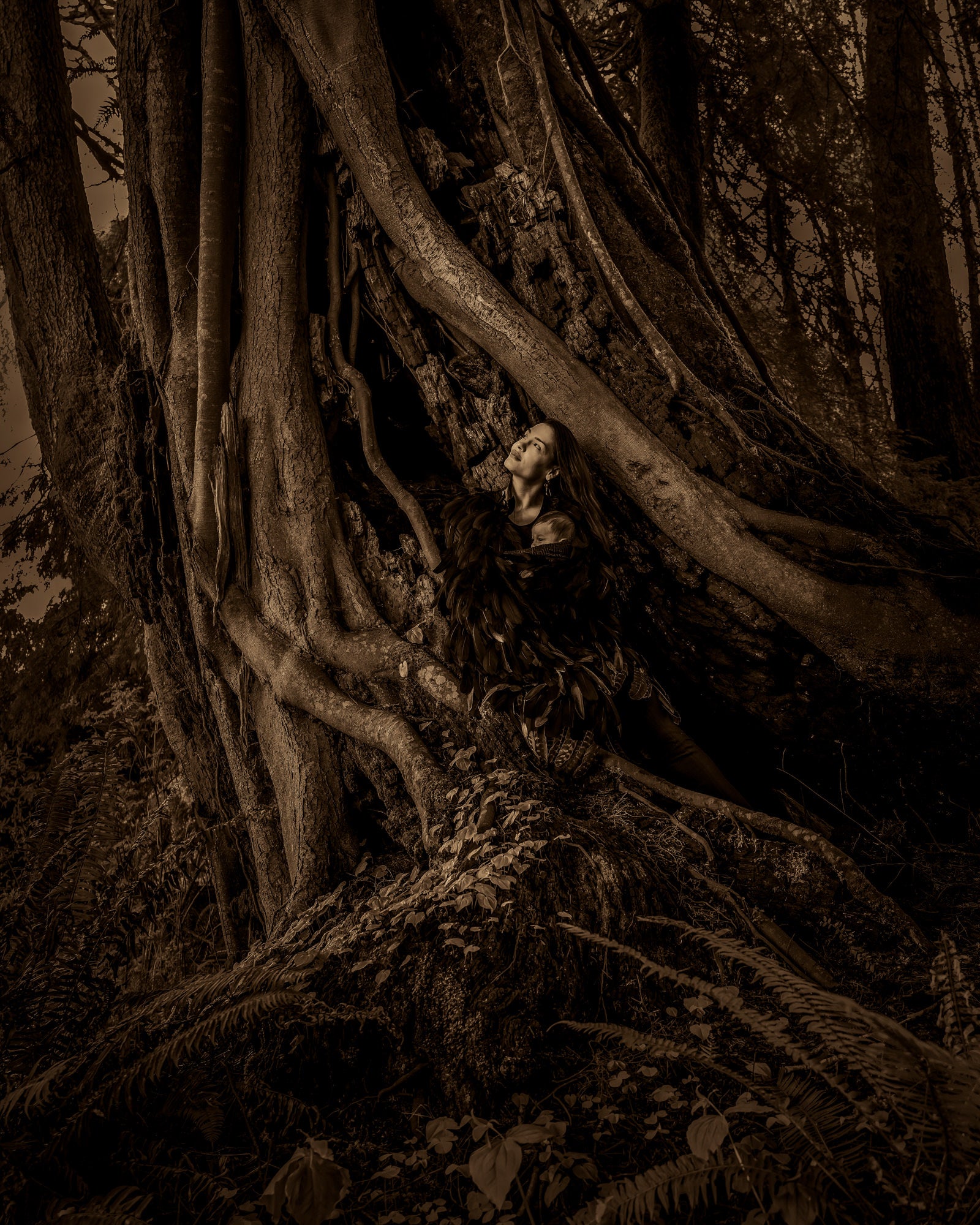

Alicia (Tsimshian Tribe)

Alicia (Tsimshian Tribe) Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7R. Sony 50mm f/1.2 G Master.

“With a nurse log beneath my feet, I can’t help but to think of the resemblance it has with our ancestors. A nurse log feeds, protects and supports the next generation. The trees, like us, gain their knowledge through the roots and hearts of the ones before them. My son - Cedar - just like his name represents strength and life. He will be strong and he will bring cleansing and healing energy. He will bring protection and shelter from the storms of life. He embodies everything our ancestors have nursed into every generation - strength, beauty, dignity, honor and resilience.” -Alicia

I thought this setting was perfect because it shows clearly that she is both with nature and of nature. The ferns come together to form a kind of nest, and her stance shows externally the protectiveness of the will of a mother.

Mariana (Yakama Nation)

Mariana (Yakama Nation) Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony RXO II.

“I think of every prayer that has ever been spoken ‘for the children, and for the ones to come,’ and I find security in knowing that the little one still submerged in the sacred waters of my womb has been prayed over thousands of times already. I nourish my womb and the growing baby with these prayers and with the mineral rich leaves of ts’uts’umslí (salmonberry). Gathered in the spring, dried, and made into tea, we’ve been drinking it throughout this pregnancy. The berries of ts’uts’umslí will be ripe when the little one growing in my belly make their journey earth-side.” -Mariana

Mariana is submerged in water holding a salmonberry branch to magnify the understanding that the baby is submerged in the mother’s own sacred water and won’t take a breath until they breach the surface of that internal ocean. The white cloth entwined around is symbolic of the cord connecting child to mother and human to spirit. Her form is relaxed and ephemeral as she reclines suspended between worlds, impressing the viewer with the knowledge that we too emerged from our own mother’s waters and simultaneously are always surrounded by the protective membrane of our collective planetary mother.

Zoe and Violet (Tlingit Tribe)

Zoe and Violet (Tlingit Tribe). Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7R. Sony 24-105mm f/4 G.

The black and white feathers on the cape wrapped around my daughter and I represent the eagle, as I am Eagle Clan, and in Tlingit matrilineal tradition, the children become members of their mothers Clan. We sit surrounded by the roots of the tree, as if it's a safety blanket around us both. This reflects the importance of our deep ties to each other and symbolizes the family tree from which we come, always providing protection. We are looking up and out in wonder of the journey ahead, the comfort and stillness of the pose suggests that any path taken, mother and child are always rooted in each other. Shortly after my daughter was born, I buried her placenta, also known as the tree of life, under a cedar tree on a winter night under the moonlight near the ocean where I live. The purpose was to ceremoniously enjoin her to Mother Earth and to ground her spirit in this plane.

Temryss and Aquila Jay (Lummi Nation)

Temryss and Aquila Jay (Lummi Nation). Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7R. Sony 24-105mm f/4 G.

“When we were waiting for Aquila’s arrival earthside, we looked to the stars, our understanding being that his spirit was making its way from the galaxy. We looked to the constellations for names and saw Aquila, meaning eagle. I come from the Golden Eagle clan of Lummi Nation so this felt good in my heart. One day, when his father and I were walking by the ocean, talking about names he said out loud, “So Aquila?” And at that moment another beach goer said, “Look! An eagle!” And there was an eagle hunting for fish, hovering straight above us. That’s how we knew Aquila, from the stars, was to be our son’s name.” -Temryss

Several tribes in the Northwest share stories of souls traveling from the stars into the womb when a child is conceived, and for a year after birth the soul remains tethered to the astral realm. When the child is a year old, it is said that they have decided to stay Earthside. This photograph was taken just after his one year birthday at Golden Garden Beach, and portrays the happiness of Aquila and his mother at his soul’s choice to stay and continue the journey on Earth.

Raven, Renae, Dem-I-Thia (Lummi Nation)

Raven, Renae, Dem-I-Thia (Lummi Nation). Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7. Sony 35mm f/1.4 G Master.

“The warm and loving embracing of our daughter, during the shoot, reminds me of what it must have felt like for her in the womb. Looking at this image of us all snuggled in the canoe, I see unconditional love, and parents who will do anything to protect her.

As an indigenous mother, it is my job to eliminate the effects of colonialism by being the one that ends intergenerational trauma that has passed down from generation to generation in Native communities. Raising my children in a loving environment, ensuring they know who they are, and where they come from, having healthy parents and a strong family. It is my job as an indigenous mother to nurture, love and teach our traditional ways, to ensure our culture will continue to be passed down to future generations. We chose to give our daughter the traditional name that I carry, Dem-I-Thia, it comes from a strong line of matriarchal women, seven generations back in my family. This is a name carried by my Grandma (Vera Lane) who is with us today, to teach and pass down knowledge to Demi. Within the next year we will be preparing a naming ceremony, to officially introduce our daughter as Dem-I-Thia to the people and the ancestors.” Hye’sh’qe -Renae

I wanted to photograph the family inside the canoe to convey the profundity this vessel has on the lives of the Lummi people. It is used for transportation, for fishing, to connect the tribe across inlets, ceremony, and for competition. It is a symbol of the survival and prosperity of Salish traditions. On the tip of the canoe is Raven’s headdress, which one day passed down to his children.

(Queets (Quinault Tribe) | Quileute | Hoh River | Elwha | Northern Cheyenne | Crow Nation)

Teleshia and children (Queets (Quinault Tribe) | Quileute | Hoh River | Elwha | Northern Cheyenne | Crow Nation). Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7R. Sony 35mm f/1.4 G Master.

“As an indigenous mother I believe it’s important that we take care of our children’s spirits. Modern medicine has its place but I will always turn to our traditional ways first. Our people believe our children have more power than us and they can see and feel more of the spiritual world than us. We are their guides. We are the ones who teach them to protect their spirits from anything that would harm them.” -Teleshia

This was so special because I got to capture Teleshia teaching her six children the ways of smudging and the importance of ceremony. The feeling was playful and excited as well as serious as they strengthened the family bond by connecting through the ancestral ways.

Samantha (mother), father and sons (Chala’ Nation, People of the Hoh River)

Samantha (mother), father and sons (Chala’ Nation, People of the Hoh River). Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony Alpha 7R. Sony 24-105mm f/4 G.

“The location of this photo is at the mouth of the Hoh river, at the rock formation known as the Praying Hands. I chose this location to honor my late mother, she had been raised in a small house nearby, although she is no longer here in person, I could feel her spirit with us, bringing me tears of happiness and a heart full of love. She would be very proud of the woman I have become, and proud of her strong grandchildren. One day, one of my sons will have the honor and challenge of leading his people as Chief. In honor of his grandfather, Chief Kila, he wears the headdress. My father created the masks worn in the photo. Just as I have and will continue to pass on the knowledge of who we are to my children, they too will pass on this knowledge to their children, the future of the People of the Hoh river.” -Samantha

At the end of this shoot, I was honored by the future chief in a beautiful ceremony and was presented with a box of salmon, abalone shell and sage.

Michelle and Mother (Tsimshian I Tlingit I Haida Tribes)

Michelle and Mother (Tsimshian I Tlingit I Haida Tribes) Photo by Zoe Urness. Sony 50mm f/1.2 G Master.

“Indigenous Motherhood is passing on traditions and my mother mastered making regalia and thankfully has passed on the traditions to her children and grandchildren. My mother had to give up her dancing days but is now the biggest fan of our dance group, the Git Hoan Dancers (People of the Salmon), a Tsimshian performance group, featuring three generations of her family. I feel so fortunate to see my two sons learn the art, carving and culture of our people, to become powerful strong dancers, carrying on traditions of our ancestors with storytelling and bringing masks to life. Becoming a Nana (grandmother) is a special love and connection and provides the best medicine. Grandchildren bring such joy and hope for our future and continuation of our culture.While we had to learn our culture as adults, we see the grandchildren learning from birth.” -Michelle

I grew up going to the same gatherings as Michelle and her family's dance group. I also danced in a Tlingit group called the Alaska Native Cultural Heritage Association and vividly remember the immense energy the Git Hoan dancers would bring to all the events. It is a special honor to be able to photograph this family and members of the Git Hoan dance group.

Continue following along as the series unfolds @zoeurness on Instagram. Inquiries at zoeurnessphoto.com.

You can be a part of our Alpha Female community. Join our Facebook group HERE and follow us on Instagram HERE.